Take a Ride on Historic Route 66

Everyone is talking about Route 66 this year – and why not. The storied “Mother Road” that has guided countless dreamers west to California is celebrating its 100 year anniversary. Over those years stories have been told, some true some imagined, but all adding to the mystic that even today makes this a must-ride road for motorcyclists from all over the world.

Route 66 today is not about efficiency. It does not exist to move traffic quickly or cleanly from one point to another. Instead, it rewards riders willing to slow down, roll through small towns rather than around them, and let the landscape – and the stories embedded in it – unfold at two-lane speed. For sport touring riders especially, Route 66 offers a rare mix of riding rhythm, historical texture, and scenery that evokes wonder about days past.

If you have not ridden it yet, the centennial year makes a compelling case that now is the moment. Here’s how to get the most from the journey.

Why Route 66 Still Matters to Riders

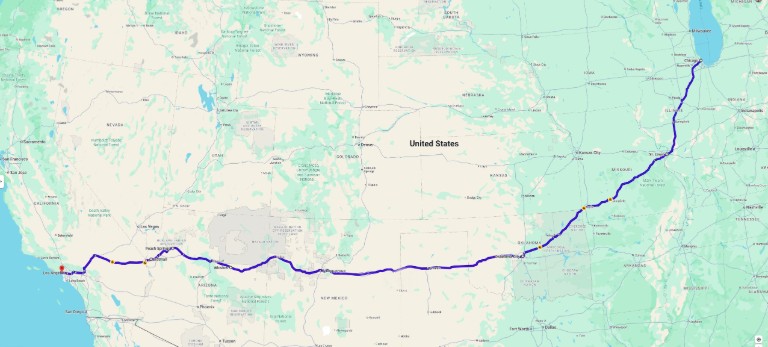

Established in 1926, Route 66 was one of the first highways to stitch the country together from the Midwest to the Pacific. Stretching roughly 2,400 miles from Chicago to Los Angeles, it became a primary artery for commerce, migration, and travel – earning its “Mother Road” nickname during the Dust Bowl years, when families headed west in search of opportunity.

But what made Route 66 special then is exactly what makes it appealing now. Long before the interstate era, the road was designed to pass directly through welcoming towns, not bypass them. Gas stations, diners, motor courts, and roadside attractions grew up to serve a steady flow of travelers. For decades, Route 66 defined what American road travel looked like.

When the Interstate Highway System arrived in the 1950s and ’60s, Route 66 slowly faded from maps, officially decommissioned in 1985. Yet it never disappeared. Large portions survived as state highways, county roads, and preserved alignments – and riders today cherish that fragmented legacy.

Unlike modern highways built for uniformity, Route 66 reflects the character of the land it crosses. It rises into high desert, drops into wide plains, threads through mountain passes, and cuts across vast open spaces where the horizon seems impossibly far away. For motorcyclists, that variation is the appeal.

Riding Route 66 Today: A Patchwork with Personality

It is important to set expectations. Route 66 is no longer a single, continuous road you simply follow end to end. In many places, it was replaced outright by the Interstate Highway System; in others, it survives as preserved stretches running parallel to modern freeways. What remains today is a patchwork of original pavement, frontage roads, and re-numbered state highways connected by modern interstates.

Although Route 66 is often associated with Interstate 44, that highway only replaces the road west of St. Louis. The original Route 66 left Chicago on a southwest diagonal, roughly along today’s I-55 corridor, before turning more decisively west past St. Louis.

For motorcyclists, that fragmentation is not a drawback, it is the defining feature of the ride. Riding Route 66 today means using the interstate as a spine to move efficiently between regions, then deliberately leaving it to experience stretches of the original road that still reward slower travel. In many of the best areas, the interstate and the historic route run close enough together that riders can easily enjoy the old road for hours at a time before rejoining the freeway.

Not every mile of old Route 66 remains drivable. Some urban runs – particularly in Southern California – were completely absorbed by freeway construction or converted into city streets. Other rural sections were abandoned and left to deteriorate and are little more than hiking trails today. The drivable part that survives, however, tends to be the most scenic, character-rich portions of the original road.

Riding Route 66 Westbound: Where the Road Still Delivers

Riding Route 66 today is less about following a single highway and more about understanding how today’s road system absorbed the old, and where to turn off to experience history. For riders heading west from Chicago to Santa Monica, the journey encompasses as a mix of interstates and preserved historic segments, with the most remarkable riding to the west, beyond New Mexico.

Leaving Chicago: Following the Modern Spine

Leaving Chicago, the modern path begins on Interstate 55, which replaced Route 66 through Illinois. While I-55 favors uninterrupted travel and routes around towns that Route 66 once passed through, remnants of the original road still surface nearby. In several places, frontage roads and signed Historic Route 66 segments parallel the interstate, offering brief but meaningful glimpses of earlier times as the route works southwest toward St. Louis and the first sustained encounters with historic Route 66.

Missouri and Oklahoma: Where Old and New Converge

West of St. Louis, Interstate 44 assumes the role Route 66 once played across Missouri and into Oklahoma. This is where the relationship between old and new becomes more rewarding. Throughout Missouri, and increasingly after crossing into Oklahoma, clearly marked exits lead to preserved stretches of historic Route 66. These sections often pass directly through small towns, where period storefronts, roadside diners, and classic signage reinforce the sense of riding through history.

Oklahoma in particular delivers some of the most continuous and satisfying Route 66 riding anywhere along the way. Between towns such as Arcadia and Oakhurst, long segments of the historic road remain intact and drivable, running parallel to I-44 but offering a completely different experience. Here, the road’s ride quality comes into focus—not in terms of outright speed, but in consistent pavement, readable sightlines, and a natural rhythm that suits a sport touring motorcycle. It is engaging without being demanding, and immersive without feeling remote.

Across the Plains: Oklahoma City to New Mexico

At Oklahoma City, riders briefly reconnect with the modern highway network, following I-35 to I-44 before transitioning west onto Interstate 40. From this point forward, old Route 66 and the interstate often run side by side. In places, I-40 occupies the original roadbed; in others, the old highway survives just beyond the guardrail, offering riders frequent opportunities to spend time on what remains of the historic roadway.

That pattern continues across the Texas Panhandle and into New Mexico. Between Tucumcari and Santa Rosa, the land flattens, the skyline widens, and the road settles into a steady rhythm that invites relaxed riding. These are miles meant to be enjoyed and not rushed. They capture the isolation and scale that define much of the western Route 66 experience without ever feeling desolate.

Arizona: Route 66 at Its Most Vivid

Crossing into Arizona at Lupton, Route 66 delivers its most vivid expression of a near-forgotten time. Long stretches of the original road remain in service, and regular roadside attractions bring the past to life. Winslow remains a popular picture stop, where a dedicated street corner celebrates Jackson Browne and the lyrics from Take it Easy that brought the world’s attention on this stop along Route 66.

West of Flagstaff, the ride becomes more engaging. Near Ash Fork, riders can leave I-40 and follow Historic Route 66 toward Peach Springs, trading freeway miles for a quieter, more immersive alternative before reconnecting near Kingman. From there, one of Route 66’s most rewarding detours begins. Leaving I-40 near Walnut Canyon, riders follow Oatman Highway (County Road 10) westward – a stretch of original Route 66 that climbs and twists through the Black Mountains. The pavement narrows, elevation changes become more pronounced, and the road demands just enough attention to keep things interesting. It is one of the rare places on Route 66 where the riding itself rivals the scenery.

The Western Finish: Desert Miles and a Mountain Detour

Descending through Oatman, on what becomes Oatman Road, the route connects with State Route 95, crossing the Colorado River into Needles, California. From there, I-40 resumes its westward path toward Barstow, closely tracing Route 66’s historic course across the Mojave Desert. The road straightens, the landscape expands, and the sense of space becomes the main attraction – especially late in the day, when the desert light softens and temperatures cool.

From Barstow, riders can choose among several routes to complete the journey to Santa Monica. Following I-15 directly into Los Angeles is seemingly direct but can be frustrating with traffic. A more fitting conclusion to a Route 66 ride is to exit near Wrightwood, follow State Route 138, and then turn onto Highway 2 – better known as Angeles Crest Highway. This legendary motorcycle road winds through the Angeles National Forest, delivering curves, elevation changes, and cool mountain air before descending toward the Los Angeles basin. From La Cañada Flintridge or via SR-39 toward Azusa, local roads lead west to Santa Monica, where the Pacific marks the end of the journey.

When to Ride: Timing and Weather

The best time to ride Route 66 depends as much on what you want to avoid as it does on what you want to experience. While the route spans a wide range of climates, its western half, particularly across the Mojave Desert, makes seasonality especially important.

Late spring (May through early June) and early fall (September through early October) are ideal. These shoulder seasons offer comparatively mild temperatures, fewer crowds, and long daylight hours well suited to multi-day riding. And since they fall outside peak summer tourist traffic, riders can enjoy a relaxed pace through towns and roadside stops.

Mid-summer riding is certainly possible, but be prepared for consistently hot days, especially from New Mexico westward into Arizona and California. Desert temperatures often climb into triple digits, and long, exposed stretches leave little relief from the sun. Planning shorter days, early starts, and frequent hydration stops becomes essential.

Winter riding can be appealing in parts of the Southwest, but higher elevations near Flagstaff and eastern New Mexico are likely to bring cold temperatures, wind, and occasional snow. For most riders, the shoulder seasons strike the best balance between comfort and accessibility.

Make It a Historic Ride

Despite its reputation, Route 66 is not a technically demanding ride. All primary and historic sections discussed here are fully paved and suitable for any street-oriented motorcycle, including sport-touring bikes. Outside of the optional detours through the Angeles National Forest near the western end of the route, riders won’t see challenging corners and trying technical roads.

That is by design. Route 66 is best approached as a scenic, experiential ride, not a test of skill or endurance. The pace is relaxed, the roads are generally forgiving, and the payoff is found in the history of it all. It is a route meant to be absorbed mile by mile, with time allowed to look around, stop often, and engage with the places it passes through.

One hundred years after it first appeared on maps, Route 66 remains relevant precisely because it offers something modern roads cannot. It connects riders not just to destinations, but to the space and stories in between. In its centennial year, Route 66 continues to remind us of a not-so-distant past.

Did you like this article?

Thank you for your feedback!

Please email the editor with any additional comments.

Your feedback is used only by American Sport Touring. We do not store or sell your information.

Please read our Privacy Policy.

by John DeVitis, Editor and Publisher

John DeVitis, Editor & Publisher of American Sport Touring, has spent years riding and writing with a focus on long-distance, performance-oriented motorcycling. His time on the road has revealed little-known routes across the United States and Canada, along with practical insights into the bikes, gear, and techniques that matter to sport touring riders. He draws on this experience, together with a background in digital publishing, to guide the editorial principles and clear vision behind American Sport Touring, delivering content riders can trust.